T wo masks. Comedy and tragedy, happy and sad. The iconic theatre masks have become a universal symbol of the theatrical arts–heck, there’s even a theatre mask emoji!

But what is the meaning of these masks? Were their faces always eternally scrunched into the juxtaposed emotions of happy and sad? Did theatrical masks have a function in addition to their form?

After you read this post, I’ll bet you will have learned some new things about theatrical masks!

Origins of those Happy and Sad Masks

Modern images of the comedic and tragic masks are inspired by Grecian & Roman masks of the 5th-4th century B.C. Their use probably stems from 6th-century ritualistic practices dedicated to Dionysus, the ancient Grecian god of wine and merriment.

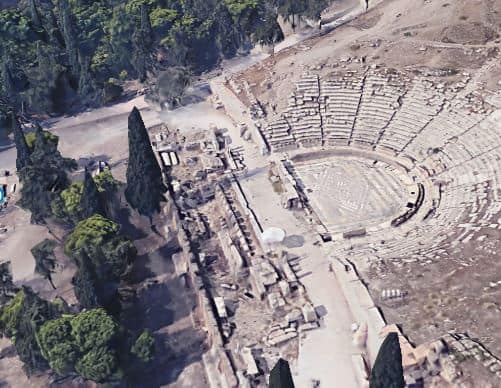

The masks were worn in the performance of public plays. Where were these plays? Most “ancient tragedies and comedies known to us were… performed at the Dionysus Theatre situated on the slopes of the Acropolis in Athens” [0].

The Dionysus Theatre was entirely outdoor and seated thousands of people . . . performing there would be kind of like performing for a middle school football stadium unamplified (using your diaphragm was a must).

When I think about ancient Grecian theatre, I picture masked performers projecting to their audience in these large outside theatrons.

Many people (including me) see reproductions/dramatizations of ancient masks and think: ‘They must’ve been crafted so expressively because patrons were so far away from the performers.’

From my reading, it seems that this explanation downplays the intricate craftsmanship of ancient Grecian masks.

Apparently, Grecian masks weren’t crafted to show one over-exaggerated emotion to a distant crowd. On the contrary, the masks’ face was mostly blank & creepy and functioned as an audience-focusing device.

The uncanny features on the masks dared spectators to gaze at the actors. Oftentimes, the masks appeared animated because of the movement of the actors combined with the optical illusion of a mask that looks eerily similar to a real face.

The more practical functions of ancient Grecian masks have to do with the transformation of an actor into a character, their performance, and the acoustics of ancient theatres. Since most articles about Grecian theatrical masks really only talk about mythology, I shall attempt to share the more functional aspects of the masks here!

Note: Though the scholarly sources I cite are, well, scholarly, most of the positions held by experts are theoretical. As is the case in all historical fields, nobody can know exactly which parts of history were lost and which parts were passed down!

The Appearance of Ancient Grecian Theatre Masks

First things first. This is what scholars believe ancient Greek masks looked like:

And this is an example of what an ancient Roman mask might’ve looked like:

Notice the difference in expression and the softer facial features of the first mask compared to the second. The Grecian mask approximation is more of a generic expression (a blank slate) whereas the Roman mask approximation is clearly emoting happily (I can also see it looking angry, but that might just be me).

“Tragic masks eventually became exaggerated into what we see in Roman times…a type of mask with ‘wide staring eyes and gaping, seemingly screaming mouth’ belongs to the later Hellenistic and Roman periods” [1.5].

Before we get to the functions of the masks, I’ll mention again that there are no surviving masks from Grecian theatre as they were made of “stiffened and painted linen” [3].

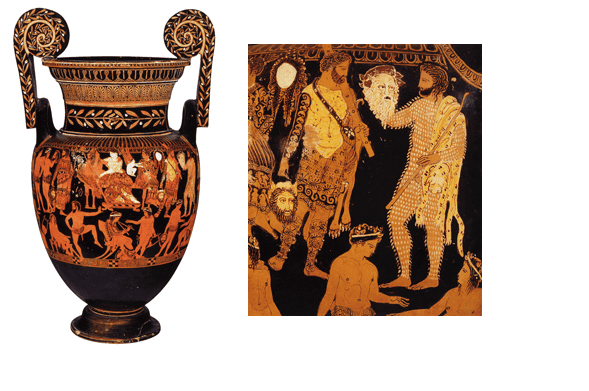

Our only resource for understanding the extent to which masks played a role in the theatre comes from illustrations of dramatic masks on vase paintings and relief sculptures [2].

One of the most famous of these vases, the Pronomos Vase (above [2.5]), depicts on one side (or ‘frieze,’ as I am told it is called) actors wearing masks and on the opposite frieze actors holding their masks.

Fascinatingly, Oliver Taplin of Oxford University proposes that “the frieze represents a curtain call after a victorious performance, when actors removed their masks and the audience recognized the distinction between theatre and real life” [4].

(If that is truly what is shown, how cool is it that the curtain call is an ancient tradition?? Not sure if they had megamixes at the end of musicals back then, though.)

Regardless of the significance of the depicted scene, the Pronomos Vase shows us the most detailed information we have about masks in the fifth century. The pictures show that the masks “had white eyes with small iris holes that the performer looked through… and seemingly left space for the performer’s own ears [and hair]” [2].

The Pronomos Vase clearly illustrates that the Grecian masks were not all simply grotesque smiles and frowns, but mimicked and accentuated certain features of the human face (while leaving others a plain blank slate).

So that’s what they might have looked like. Now, the (theories) for why they were how they were!

Why Wear a Mask? Creating a Focal Point.

Have you ever seen an inanimate object that looked like it had a face? Or one of those new AI robots that move and talk so convincingly that you do a double take when you realize they’re not humans?

This uncanny feeling was utilized in the design of Grecian masks to get the audience to focus on the actors and to encourage the spectators to project their own perceptions of what emotion the actor was portraying onto their mask.

According to Peter Meineck, “the tragic mask mediated a bimodal ocular experience that oscillated between foveal (focused) and peripheral vision, and in the eyes of spectators seemed to possess the ability to change emotions, and that these qualities of the mask were fundamental to the performance of the tragedy and the development of narrative drama” [2].

Basically, the generic expression on the mask allows it to be seen by the spectators as many different expressions / emotions.

**It’s worth noting that actors playing multiple parts would change masks.

Though these masks made it impossible for the actor to convey facial emotions in a natural, everyday-life way, to Meineck it is clear that the ancients crafted masks with their vaguely-yelling-yet neutral faces to encourage emotional responses and empathy from their audience. (Who knows…they probably could have animated the masks in some way if they really wanted to).

Without animatronics or incredibly elaborate sets/costumes (a la modern-day performances), actors had to draw attention to the play somehow. After all, an outdoor performing environment is overwhelmingly overstimulating compared to the manicured modern proscenium arch stage.

I think Meineck is spot on when he states that masks were “the focal point of the entire visual experience of watching theatre.”

Masks were the critical tool to encourage the audience to focus in on the show.

“On the southeast slope of the Acropolis with its panoramic views of the city, countryside, and sea…dramatists became highly skilled in manipulating the interplay between peripheral and foveal vision, offering a multilayered visual experience” [2].

Think about the last time you saw somebody in a mask. It immediately draws your attention, right? On Halloween, I can’t stop staring at spooky mask-wearers. The same uncanny manipulation of focus applies to masks worn during performance–especially those that are crafted with illusion and transformation in their design.

The Illusion of Theatre Masks

The build of the masks heavily influenced the audience’s perception of and focus on the character onstage. I’m not going to go too deep into it here (seriously, you should read Meineck’s journal article), but he mentions a couple of important characteristics of the masks that contribute to the transformation of the actor.

The first is the utilization of feminine masks for male actors. Women were not allowed to perform, so the masks men wore had to communicate gender as well as emotion.

“A white face usually indicates a woman on a Greek vase” and “the female mask is in much higher contrast than the male masks.” This visual contrast “is a key factor in determining the gender of a face” [2].

So there’s a good chance that the real-life masks that portrayed females had more contrasting colors and features than the male masks (I’m sure the costumes the male actors wore also contributed quite a bit to the goal of getting the audience to pay attention!)

Another part of theatrical masks’ illusion is the physical depth of the mask.

In a study using traditional Japanese Noh masks, a single mask was “tilted in different directions and subjects were asked to report the expression” that they perceived the mask was illustrating.

The responses changed with the various angles of the same mask. “The researchers of the Noh mask experiment noticed how certain features of the mask were fashioned to enable it to change its expressions depending on the aspect.”

The protruding lips and highly visible sclera (white of eyes) on many Grecian (and Noh) masks work with the actors’ movements and words to focus the audience’s gaze and communicate their story.

Just for fun, here are some more examples of artwork that transforms based on different contexts, peripheral vs foveal vision, and different angles:

The Mona Lisa. Is she smiling or not? Try looking at her mouth directly and then focusing on the background. I usually see her smiling but occasionally she’s frowning!

THE DRESS. Just look at it. What are the colors of this dress? #whiteandgold or #blueandblack (it is lavender and black, clearly. . .)

Okay, back to optical illusions demanding spectators to focus on actors in masks:

“The gaze direction of the Greek mask may have been an important factor in establishing reciprocal gaze between spectator and performer, one in which emotional states could be easily communicated and the viewers’ mirror neuron responses would have created feelings of empathy with the masked fictional character presented before them.”

Though these theatre masks are not physically animated (other than flowing hair of the mask/actor), they were crafted to give the illusion of movement and emotions. The audience is drawn to look at a mask because of how uncanny its resemblance to an animated, human face is. And then, they project the emotions they hear the actor proclaiming onto the physical mask itself!

Now let’s look at a picture of the classic happy and sad masks:

Now think about the possibility that in Grecian theatre multiple emotions were portrayed by a single mask. This theory makes the classic happy and sad masks look kinda lame. I mean, why change masks when your mask can be so ambiguously expressive the audience will go ahead and fill in the emotion for you?

In all seriousness, though, mad props to those ancient actors. They had to focus on their lines and choreography AND incorporate the mask’s angle and appearance into their performance.

Fun fact: The only time I have ever worn a ‘mask’ during ‘performance’ was when I was a cow mascot for the Fort Worth Stockshow and Rodeo. Every time somebody took a picture with me, I unconsciously smiled. I wonder if the ancient Grecian actors also smiled under their masks . . .

Finally, their masks were probably crafted to enhance the acoustics of the theatrical space…

The Acoustic Functions of Theatre Masks

“Theatre is a visual phenomenon as well as an acoustic one” [0].

Think about the last theatrical show you attended.

Were the performers mic’d? Was the show indoor or outdoor? Was there a mishap with the sound, or was it so flawless you never even thought about how you were hearing everything?

As a band nerd as well as a musical theatre enthusiast, every musical I attend gets a thorough examination from me of its balance between the orchestra and performers’ amplification.

Obviously, nobody wants to hear a bad singer / band. That hurts our ears.

But even more tragic (in my opinion) are fantastic performers who are unable to be heard!

Whether it is because the performer is not projecting enough, their microphone is late turning on, the band is not properly situated in the space–it absolutely takes me out of being engulfed in a performance.

So how did the ancient Greeks perform in giant theatrons and make sure everybody could hear them? For one thing, they created masks that would focus the spectators’ vision (if your audience isn’t paying attention, they’re definitely not hearing anything!)

For another thing, the masks are commonly believed to have enhanced the amplification of certain frequencies in actors’ voices.

Here’s my summary of a group of engineers, an audiologist, and a dramatic institute professor’s research on the topic:

Listening

As I mentioned above, there is evidence to suggest that Grecian masks had eye holes the size of human pupils. “The minimization of the sight… leads the actor to the act of akroasis, the act of conscious and active listening” [6].

As directors across the globe will tell you: you can be the best monologuer in the universe, but if you are not actively listening in a scene with others, your performance will lack realism.

It’s fascinating to me that just as Grecian spectators focused in on the mask as the focal point of transformative emotions (a blank, mostly expressionless canvas), so too did the actors hone in on fellow performers’ masks to create that strong onstage connection.

The Theatre’s Acoustics

The ancient theatre that is the most intact today is Epidaurus which was “perfectly tuned for the performance of ancient drama” as a “result of an evolutionary design process” allowing performers to be heard as far as 60 meters from the source!

I am not an acoustical expert, so I’ll let them do the talking about this:

“from any sound produced in the orchestra, the geometric shape of the theatre generates reflected and scattered sound energy which comes initially from the orchestra floor and then periodically, from the hard reflecting limestone surfaces at the top and back of a number of seat rows around the listener position. The main bulk of this reflected sound energy is acoustically beneficial since it arrives at the listener’s ears with very short delay (within 40 milliseconds) after the direct signal and as far as the listeners’ brain is concerned, the early reflection sound is also perceived coming from the direction of the source at the stage. In this way, the strong reflections fuse with the voice which is perceived to be significantly amplified.”

Basically, the ancient Greeks were math and physics #nerds and built the Epidaurus theatre to bounce sound waves off the back of the theatre’s seats efficiently.

Combining the Physical Theatre’s Acoustics with the Masks’ Acoustics

(If you would like to see the actual calculations (including a big ole Sigma equation, azimuth angles, and anechoic speech), I suggest you check out their article)

After these experts did all of their real-life measurements and simulated calculations (simulations were necessary because the theatre house at the back of the theatre of Epidaurus is now a crumbly pile of rocks), they found “that the masks amplified the spectral region up to 1000 Hz.

This effect was found to be stronger around the male speech fundamental frequency. Given that the theatre responses present a significant peak around the mid 1000 Hz region, the ‘mask-filter’ effect appears somehow to smooth the overall spectral profile of the ‘theatre-filter’. Furthermore, the masks would alter the actor’s voice by boosting the low-mid region of speech reaching the audience” [6].

So, the masks amplified the frequencies that played nicely with the theatre’s already fantastic acoustics. Those ancient Greeks meant acoustic business!

Final Thoughts on Ancient Theatrical Masks

Before writing this post, I honestly had no clue about the form and function of ancient Grecian masks. Perhaps I still don’t because scholars do not have a physical ancient Grecian mask to base their research on.

I do believe these scholars’ findings as they have done much more research than I (not to mention, the ancient Greeks did a lot of cool stuff, so why would they not make their theatres acoustic marvels?)

I also did not go into everything Grecian mask in this post–I’m sure there are plenty more journal articles all about the specific characters and archetypes masks represented in ancient plays that you could read!

I’ve certainly enjoyed learning more about the origins and use of masks in ancient Grecian theatre, and I hope this post has enlightened you a bit on the topic as well.

Have a lovely day!

Grace

P.S. I am not an historian, just a lay researcher intending to share what experts say about the history of the quintessential ancient Grecian theatrical masks. Please do not hesitate to correct me (charitably) if I shared a mistake!

[0] Mask, Actor, Theatron and Landscape in Classical Greek Theatre by Thanos Vovolis

[1] The Story Behind the Comedy and Tragedy Masks

[1.5] The Greek Mask

[2] MEINECK, PETER. “The Neuroscience of the Tragic Mask.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, vol. 19, no. 1, 2011, pp. 113–158. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41308596. Accessed 6 May 2020.

[2.5] Classical Art Research Center

[3] The British Museum Greek Theatre Mask

[4] The Pronomos Vase and its Context

[5] Behind the Scenes in The Lion King’s Puppet Shop

[6] The Sound Effect of Ancient Greek Theatrical Masks